Maps

Maps are not just the illustrative or decorative elements that they are still often treated and used as – not only in films, but also there. They fulfill an important function with regard to both the spatial and temporal classification of events. They provide orientation and convey important information that – otherwise they could be dispensed with – could not be conveyed in any other way, or not so easily or quickly.

Maps are always abstractions and thus always radical reductions of reality. They select what is shown as well as what is not shown. Maps usually only show a part of the earth’s surface, and the selection of the map section already guides and directs the view to what is considered essential. The selection of what is shown and what is not shown determines how the map is read.

The design of the maps in the film is therefore of crucial importance. Geographical and historical precision is just as crucial as the selection of design elements, geographical information and color implementation that are considered essential.

Almost no movie that uses maps has maps that are free of errors

In the German film „Sorry Genosse“ („Sorry Comrade“) (2022) by Vera Brückner, which tells the story of a woman’s escape from the German Democratic Republic (GDR, in German: DDR) to West Germany (FRG, in German: BRD), there are two maps. Both cards were made especially for the movie.

One shows parts of central eastern West Germany and south-eastern East Germany in the 1970s. With its high degree of abstraction and radical reduction to the essentials, the map is clear and easy to grasp. The country abbreviations FRG and GDR are printed in large bold type to facilitate orientation and provide an overview of the selected map section that is as quick to grasp as it is easy to understand. The Eastern Bloc, i.e. the GDR and Czechoslovakia, which can be seen to some extent at the bottom right of the picture, and the Federal Republic are clearly separated from each other in color, and the Iron Curtain forms the main graphic element as a bold red line in line with the story told. The border between the GDR and Czechoslovakia is correspondingly much thinner and less prominent in black.

Historical and contemporary country and city names

On the monochrome surfaces, both in the east and in the west, there are individual smaller and delimited fields, which are strongly stylized and – thus stylistically quite appropriate and successful – suggest tree areas in the style of school atlases of the 1970s. However, these elements have no connection with the actual location of larger areas of forest.

Only a few larger cities are marked to make orientation easier. Chemnitz can be seen on the right. However, the city was called Karl-Marx-Stadt from 1953 to 1990 – and thus also during the period depicted. It would have been better to show today’s Chemnitz with its former name.

Another map can be seen in the same film, which is similar to the previous one in essential stylistic elements, but now shows south-eastern Europe. Once again, the Iron Curtain is marked in bold red, while the country borders are narrower and marked in black. Romania is highlighted in green and the country name is in a larger font than that of the other states.

However, the national borders shown do not correspond to those of the 1970s, when the story shown here takes place. Instead, all the borders shown here are those of the present day when the film was made in 2022.

All the names of states and cities are also shown in English, which in a German film at least raises the question of why.

In addition, a number of rivers are shown in Romania and to some extent in the neighboring areas, but these end in nothing, as the Danube, the largest river in south-eastern Europe, and its tributaries in the other countries are missing.

It would have been better to show the borders at the time and to name the countries according to their names and spellings at the time, either in the respective national language or in German. So Austria and Vienna instead of Austria and Vienna; Czechoslovakia instead of Slovakia; Soviet Union instead of Ukraine; Hungary instead of Hungary; Romania and Bucharest instead of Romania and Bucharest; Bulgaria instead of Bulgaria; Yugoslavia and Belgrade instead of Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Belgrade.

Although Yugoslavia was on this side of the Iron Curtain, as a socialist country it was also to be colored red. In addition, both Zagreb and Bratislava were no longer to be marked as capitals with a framed square, but only with a simple black square. All rivers should also either be uniformly included or deleted from the map.

The exact course of historical borders

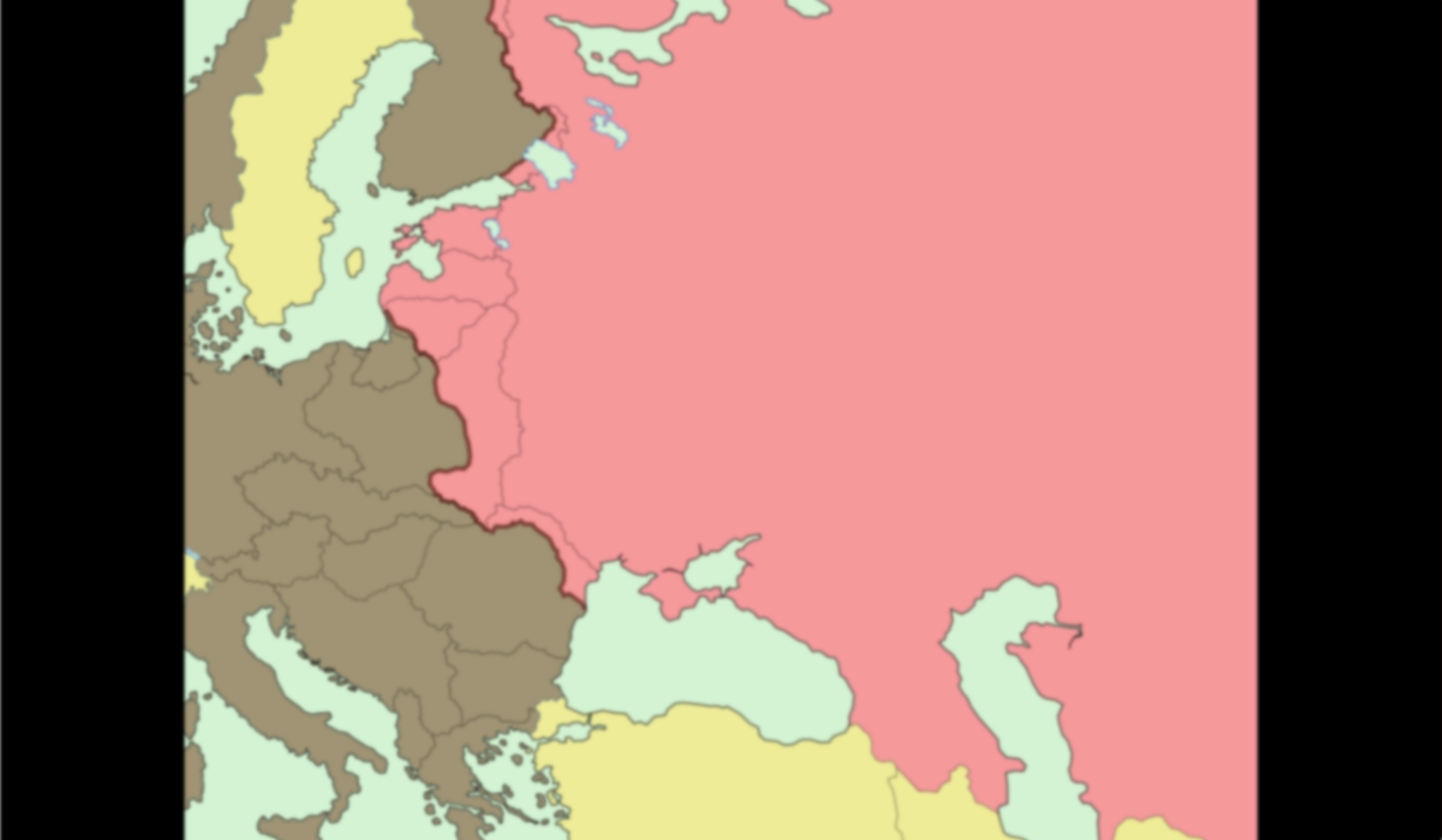

In „Jeder schreibt für sich allein“ („Everyone writes for themselves“) (2023) by Dominik Graf, there is a map depicting Central and Eastern Europe on the eve of the German invasion of the Soviet Union.

With its reduction to four essential colors – red for the Soviet Union and the territories and countries annexed by it until June 1941, brown for Germany, its allies and the territories and countries occupied or dependent on them until the summer of 1941, and sandy yellow for the neutral states and a light blue-green for the seas – this map can also be quickly surveyed and its message quickly grasped. Labels are not used.

This map shows not one, but two temporal states. On the one hand, the borders of the two major power blocs in the first half of 1941 are shown, clearly highlighted in color. Secondly, the borders of 1937 are shown, marked with narrow lines. The map thus makes it clear that, in accordance with the general basic message of the film, all border shifts from 1938 onwards are considered illegitimate.

However, the border of Albania, which is wrongly attributed to Yugoslavia on the map, is missing. The German-Danish border is also not shown. The borders of East Prussia and the Free City of Gdansk are also missing, both of which erroneously appear to belong to Poland.

In addition, the map shows the Yugoslav-Italian border not in the interwar period, but after the Second World War. The same applies to the Finnish-Soviet border, which shows the situation not before but after the Winter War of 1939/40. The north-eastern border of Romania is missing and – at least partially, the map is quite inaccurate at this point – the extension of the Soviet sphere of influence to Bessarabia, which was occupied by the Soviet Union after the Hitler-Stalin Pact. Southern Dobruja, which Romania also had to cede to Bulgaria in the summer of 1940, is not listed here as Romanian territory, but already as Bulgarian territory. The Klaipėda Region, which was separated from Lithuania under German pressure in 1939 and incorporated into the German Reich, is also not colored brown on the map. In addition, the Swedish island of Gotland is not yellow, but incorrectly colored brown.

It is also not clear why the southern boot tip of Italy and Sicily as well as the south-eastern Soviet Union are colored lighter.

Fictional maps

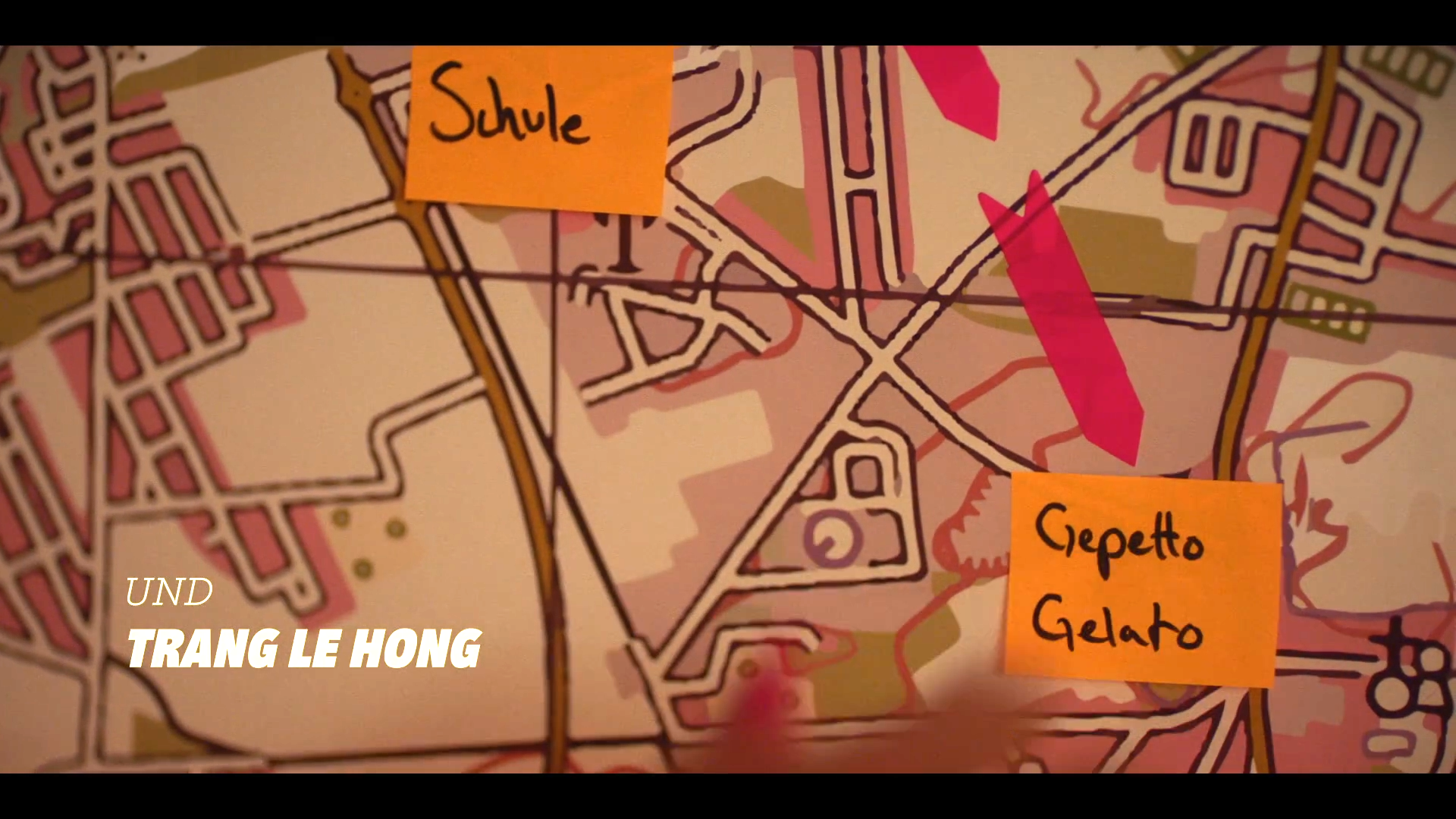

A very nice example of an extremely successful design for a fictional map, on the other hand, can be found in the German TV series „Doppelhaushälfte“ („Semi-detached house“) (2025) by Dennis Schanz.

The map shows the fictitious town of Schönefelde near Berlin, where the series is set, and it was converted by Tracy into a map of her master plan to build a bubble tea empire in the town.

Tracy has marked the locations of her future stalls and her expansion plan with Post-its, flags and arrows stuck on strategically important places, creating a veritable military order of battle.

Although the map can only be seen for a few moments in each of two scenes, great care was taken in its creation.

In an A1 format, as was common for the end of the 20th century, it shows the town with all the typical features of such a map. Roads and paths of various types, railways, built-up areas, green spaces, industrial areas and wasteland are shown in the typical way and correctly in the corresponding colors, and the heading „Schönefelde und Umgebung“ („Schönefelde and surroundings“) indicates which place is shown on the map.